“Two quite opposite qualities bias our minds—habits and novelty.”

– Jean de la Bruyere.

Although known for his satires, the French philosopher’s quote above should be seen as an honest piece of advice for investors. Morningstar reports that professional Canadian fund managers tend to show home bias. In other words, most are pursuing old habits by having an overabundance of domestic securities rather than novel, global investment opportunities.

In even simpler terms, they may not be as diversified as you’d hope. Let’s discuss the downside of home bias and how to avoid it for more resilient portfolio construction.

The Home Bias Report by Morningstar

The data is immense and, for our purposes, too long to summarize in detail. If you’re interested in reading it in full, you can do so here and here, but we’ll cover the basics too:

- 14 markets were studied, from Canada to Hong Kong.

- Canadians favour equities over fixed income, but home bias is stronger for the latter. Canadian stocks represent 30% of portfolios, which is much higher than the nation’s weight in the broader global equity market.

- Notably, personalized investments like model portfolios (such as our own) are sparse when compared to Canada’s peers.

- Home bias is likely to be troubling for equity investors, as Canadian markets lag global ones. If currency was hedged, fixed income did not face these same challenges.

- Over the last decade, a $10,000 investment in the Morningstar Global Markets Index would have seen an additional $7,500 in returns compared to the same investment in the Morningstar Canada Index.

- Prior to that, however, the Canadian index performed better than its global counterpart.

Why Home Bias Exists

If you’ve never heard of it before, home bias is one of the better-known behavioural drivers of investment styles. The reasons are largely psychological, but perhaps not exactly logical. In Michael Dobson’s own words, building a portfolio with a disproportionate amount of domestic stocks and bonds is “not rooted in sound investment rationale.”

It’s reasonable to assume investors know their home countries better than ones they’ve never visited before, and that perception extends to choosing stocks as well. If they know the company, are customers, or hear about it on the radio, they’re likely to assume they have a better grasp of the business. Investing, however, requires research—buying a new shovel from a local hardware chain probably isn’t as effective as researching a foreign company’s fundamentals when it comes to investing.

We’re keen believers in keeping more of what you earn by reducing your tax liabilities on returns. Registered accounts (RRSP, TFSA, FHSA, etc.) are an excellent investment vehicle when used appropriately. For non-registered accounts, however, people may gravitate towards qualified investments that are taxed more favourably by their governments.

That being said, to keep more, you may need to make more—a high dividend-paying stock from a U.S. corporation may provide higher returns than an underperforming Canadian, even after applying the dividend tax credit. Further, you can consider holding it in an RRSP for the tax advantages it provides. In a previous post, we wrote about tax-efficient investing and discussed the diversification of assets between different accounts.

The Downside of Home Bias

After reviewing 3,000 funds, it seems that professional investment managers are not immune to home bias. This is somewhat surprising—with far more resources, experience, and acumen in their field of work, a realm of global opportunities is being sidelined in favour of Canadian investment products.

In fact, fewer than one in ten global balanced funds has similar (or less) exposure to Canadian stocks than the Morningstar Global Markets Index. For fixed income, the differences become even more dramatic: approximately 95% of funds showed an increased home bias for Canadian bonds when compared to the study’s benchmark.

As stated earlier, this likely hindered portfolio returns for investors and fund managers alike. If managed properly, domestic bonds could keep pace with foreign ones through currency hedging. The concept is not overly complicated at face value (hedging against currency fluctuations to minimize the influence of conversion rates and, in turn, volatility), but it becomes more difficult for investors without a keen sense of global economics, and forecasting currency movements can be extremely difficult. Those who failed to account for how currencies can impact returns experienced unnecessary volatility.

The Benefits of Diversification

Canada has its own issues to deal with, and it seems they aren’t in a rush to leave. As a country heavily reliant on commodities (such as oil products, our chief export), we are susceptible to slowing economic growth or global trade. This is a basic example of the risks of home bias to show why diversification is such a key tool—your portfolio should not rely on a single sector, region, or asset class.

Over the past ten years, Canadian stocks have lagged global markets. What makes it more interesting, then, is that the decade prior showed the opposite. While one could try to time the highs here at home and sell before the lows, timing the market is not nearly as important as time in the market. The losses can be staggering, and while the potential for attractive returns exists, the associated risks likely outweigh the benefits.

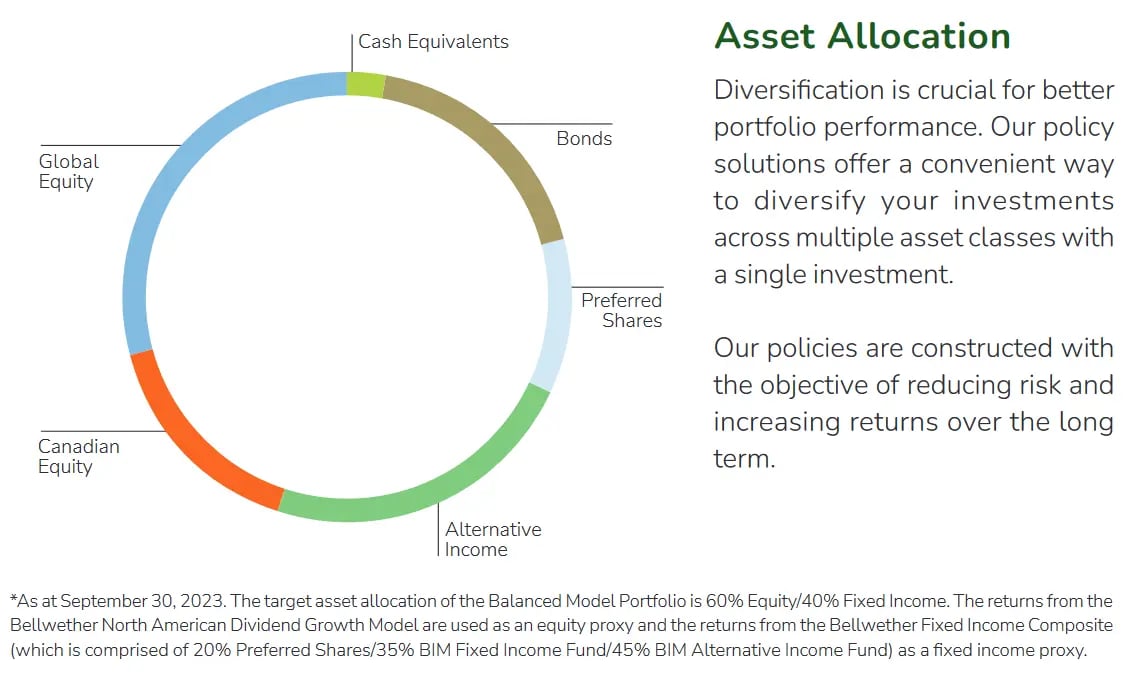

Geographic exposure can be just as important as sector exposure for your portfolio. As of September 2023, the equity sleeve of our Balanced Portfolio’s global exposure is almost double that of our Canadian weighting. When it comes to diversification and identifying opportunities, we invest globally in quality companies with strong track records.

Investment decisions should be rooted in beyond-borders logic, not at-home comforts. We prefer to have a global presence—when one country is overperforming or underperforming, its peers even the scales.

Next Previous