“We are all gifted. That is our inheritance."

– Ethel Waters

Starting her career during the 1920s, Waters quickly moved from singing the blues to performing on the Broadway stage. While her quote is an uplifting thought, it serves as a useful starting point to discuss estate planning—after all, a family trust intended to soften the tax implications of inheritance all starts with a gift.

What Is a Family Trust?

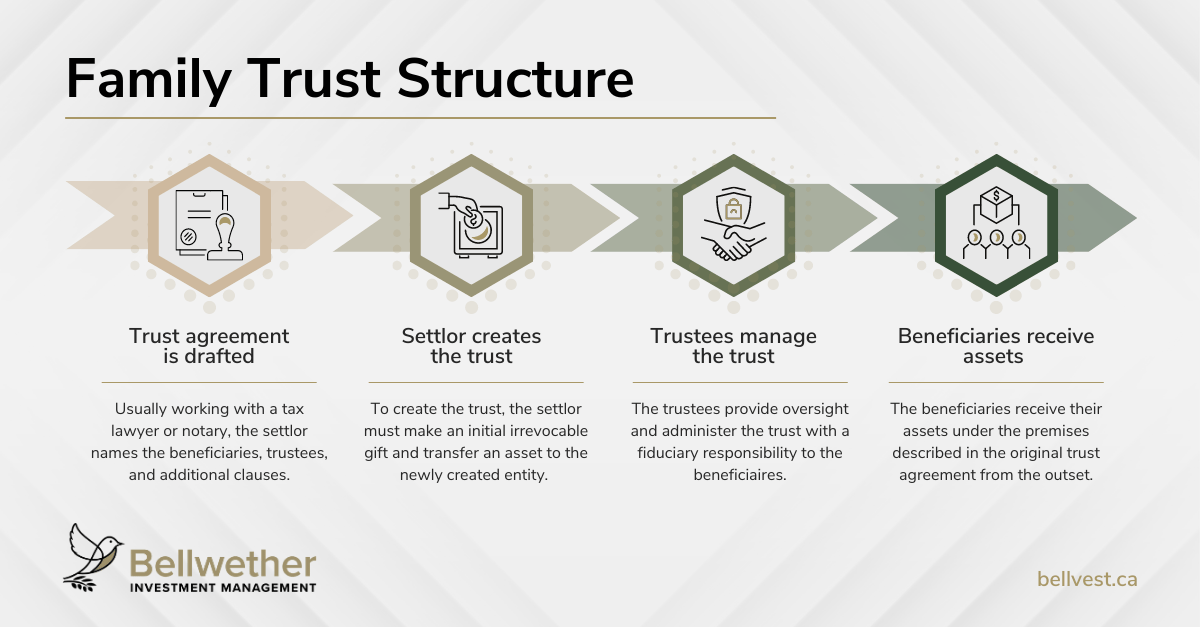

By definition, a family trust is a legal entity that can hold assets and enter into contractual agreements with third parties once it is formed. This may sound confusing, but in essence, the trust is designed to allow the settlor (creator of the trust) to legally transfer their assets, real or otherwise, into the possession of the trust itself.

Once they change hands, these assets are administered and distributed by the trustees to the named beneficiaries in the trust agreement. You can think of it like receiving a Christmas gift from your parents, but instead of passing it on themselves, they have their lawyer facilitate the handoff.

What Are the Advantages of a Family Trust?

There are a number of enticing advantages that make family trusts popular tools for estate planning and optimizing wealth distribution in a household. Aside from easing the path of wealth transfer using a structured trust agreement, there are several other benefits as well.

Not only can a trust help protect your children’s future and help you leave a legacy, it can also help safeguard your assets themselves. Should the settlor of the estate (or the beneficiaries) have creditors nipping at their heels, properties held within the trust are shielded and cannot be seized. That being said, a trust must be founded in good faith, if done for alternative reasons, this can lead to a judge calling for the seizure of assets.

Although Canadians are lucky enough to avoid inheritance taxes, there is a caveat. Taxes are applied before the estate can be distributed as if the deceased were still alive and paying their dues. This process outlined in the Income Tax Act, is called deemed disposition, which mandates that certain properties are to be treated as if they had been disposed of (sold) at market value at the time of death, even though no sale has taken place. From this figure, capital gains (the difference between the market value and sale price) can be calculated accordingly, which can be taxed at 50% of said gains.

An estate, however, is fundamentally different from a trust. While the former allows for a one-time transfer, the latter creates an ongoing arrangement; all capital gains are earned by the trust and, as a result, are not taxable at the point of death. To prevent underhanded moves of indefinite tax postponement, a disposition is forced every 21 years, commonly known as the 21-year rule. While taxes are still applicable at one point or another, having over two decades to better situate yourself and the tax implications allows for greater maneuverability.

Trusts can hold and sell corporate shares that utilize the qualified small business corporation (QSBC) exemption, which can interact positively with the lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE). As of 2023, the total LCGE available for each Canadian taxpayer weighs in at $971,190 (indexed to inflation) in tax credits. These terms may sound complicated, but in theory, the trust could sell a significant amount of QSBC shares and distribute the profits to the beneficiaries. Each and every one of them would be able to receive up to $917,190 tax-free if they had not previously claimed the LCGE.

Taxes can be further managed through income-splitting. On a basic level, by splitting the assets in the trust between your beneficiaries, you may incur fewer taxes compared to centralizing the income. In a more sophisticated manner, income can be shifted away from higher-earning family members to others with a lower marginal tax rate. As a popular and clever way to legally avoid taxes, Canada introduced rules on how split income can be taxed via attribution laws. In essence, subsection 75(2) of the Income Tax Act allows the CRA to “attribute” taxable income back to the family member who provided the initial capital for the investment and nullify potential tax savings.

Income splitting is still viable, but with attribution guardrails in place, it is much less accessible to those without an extensive understanding of tax laws. It is always suggested that you contact a professional to find out if income splitting is a suitable—and legal—option for your circumstances. The key to navigating these murky waters comes down to how your trust is structured. A few considerations for you to keep in mind, should you be interested in income splitting and dancing with subsection 75(2), are:

- The settlor should not be the sole trustee, and a third party at arm’s length should be included.

- The settlor should not be a listed beneficiary.

- In the case of a loan being made to the trust, it should be a bonafide loan.

- No investment powers should be delegated to the settler.

- The settlor should be one of three (or more) trustees where verdicts are dictated by majority vote processes at all times.

What Are the Disadvantages of a Family Trust?

As mentioned previously, the 21-year rule reminds us that the tax bells will eventually toll for every Canadian, trust or otherwise. It isn’t truly a disadvantage, as it does provide more flexibility compared to some alternatives. Similarly, even family trusts with the purest intentions can cause rifts between beneficiaries; this is sadly the reality that most forms of inheritance must wrestle with.

More tangible disadvantages include the significant administrative requirements and recordkeeping. Income generated by trusts is taxed at the highest marginal rate, and T3 returns must be filed for most trusts due to new legislation introduced in Budget 2018. Trustees are expected to document their work and account for the administration of the trust and any tasks performed for it, as well as produce financial statements.

Is a Family Trust Right for Me?

Due to the nuances associated with establishing a family trust, there is no universal answer. In broad strokes, the general concept of a trust may work for one family but not for another. This may come down to several factors, such as the size of the estate, the number of potential beneficiaries, and the associated expenses.

With a more detailed brush, the specific structure of how the trust is established will be tailored to the family in question, and it is incredibly rare to see identical trusts. Estate-freezing clauses for growth-oriented business owners are unlikely to function as efficiently for a family looking to make their current savings into a legacy for generations to come. Some trusts may issue payments over the course of ten years, whereas households with members incapable of working may last much longer. Certain beneficiaries may vote to have their trusts wound up sooner, and others might one day come face to face with the 21-year rule.

When a trust is created, the best ones are fine-tuned to the distinct needs of the family itself. If there is only one concept you can take away from this article, let it be this: incorporate a professional to help you at every stage of the journey.

At Bellwether, our Family Wealth Advisors have the necessary expertise to assist you in setting up trusts for you and your family, and to help you plan for the future so that you can leave a legacy for your loved ones.

Next Previous